I sent this memo to the Scale AI team back in 2019. At the time, I viscerally remember the magical feeling that we were going at warp speed, and I didn’t want that to go away. This memo was my manifesto to continuing warp speed. I hope it’s helpful to anybody who wants to make a big dent on the world.

When candidates ask what keeps me up at night, my answer is the fear that we lose the high-alpha execution of a startup and slow to the pace of a big company. The goal is that the Nth employee is able to be just as effective and impactful as the 10th. There are a number of reasons why that isn't true at most companies, and I wanted to explain one of them below.

Scopes and optimism significantly impact how quickly shit gets done, due to a combination of how humans work and bugs with common incentive structures. Scopes, in an engineering context, are time estimates for how long things will take to finish. They are produced for planning purposes, so that we can plan ahead for how long things take and figure out how much stuff we'll get done.

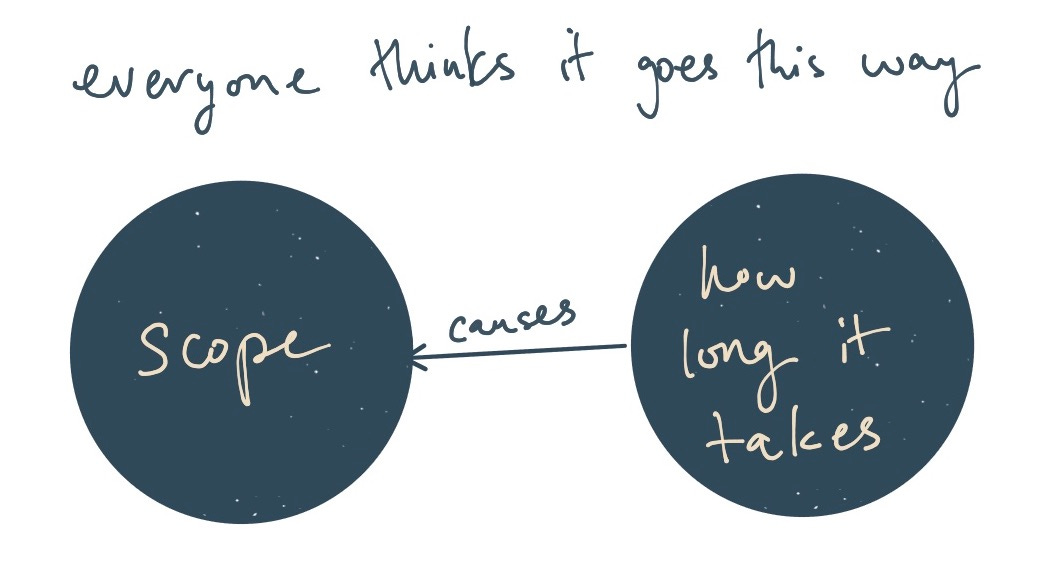

While definitionally it seems like how long things inherently take to get done influence the scope, the causality actually mostly goes the other direction.

The scope influences how long things takes. When we say things will take a long time, they will take a long time. When we say things will take a short amount of time, they will take less time.

To begin justifying my claim, see below a histogram of about 9 million marathon finishes. Zoomed out, it looks like an approximate Gaussian distribution, which is roughly to be expected. But, when you look more closely, you'll see there are noticeable large spikes in the distribution at “round numbers”, at 3:00, 3:30, 4:00, 4:30, etc. These spikes aren't by accident; they're produced because humans naturally try very hard to hit goals, and we become very good at adapting to these 0-1 loss functions.

[Another example is the 4 minute mile. TL;DR Everyone hypothesizes a sub-4 mile is impossible. One man runs sub-4. Subsequently, lots of people start running sub-4.]

A version of this that we all have seen is the student completing assignments right before the deadline. Almost everyone I know completes homework right before the deadline, even when they really enjoy the homework. The existence of the deadline warps their distribution to finish it right before the deadline most of the time (sometimes right after).

One way to put this is that people are really good at metaphorical limbo. No matter where we set the bar, we're great at being just under it. I'll call this the Limbo Effect.

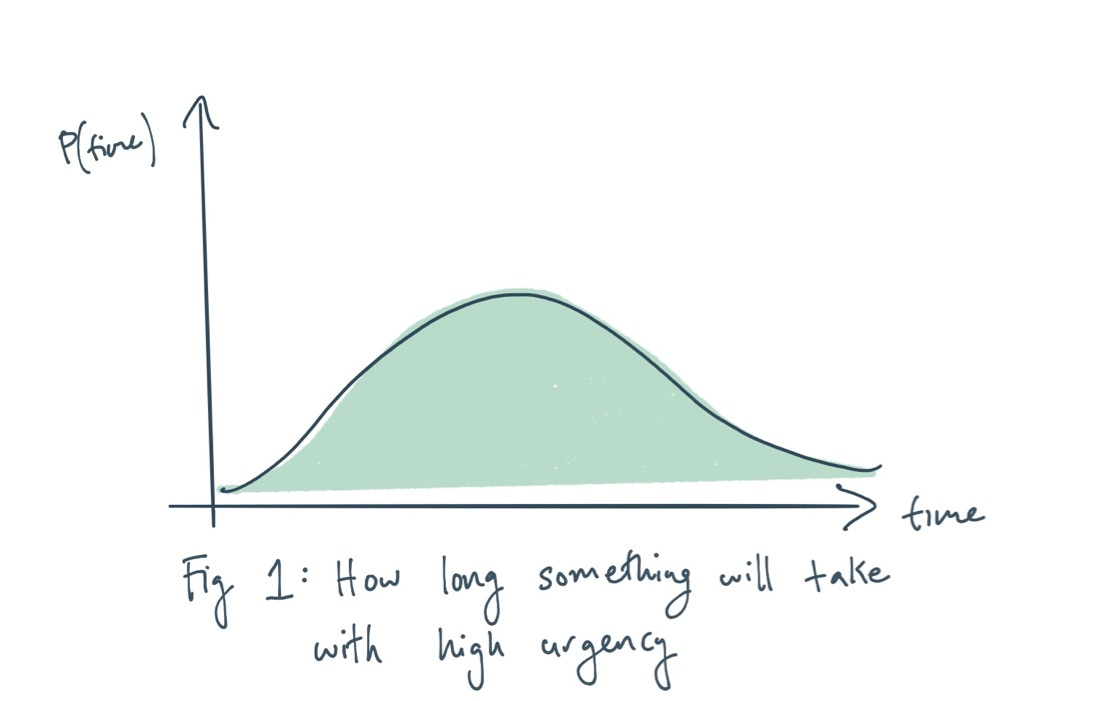

Let's see how this affects the startup. Let's first consider how long something takes in a “high urgency” environment—one example is during site downtime. Every moment the site is down is really bad, so the incentive is to finish it as fast as possible. Another high-urgency environment is an early-stage startup. In most scenarios, the company dies and fails, so every moment that new stuff isn't accomplished is really bad. There aren't really “deadlines” in both environments—the deadline is now.

Let’s model the time it’ll take to do as a Gaussian—most things are generally Gaussian, and we're just trying to get it done:

What happens when we set a “realistic” scope? Let's assume we know this distribution exactly, and we set a scope that is the median of that distribution. The existence of the scope means that we're now planning for that amount of time to be taken, so the incentive structure actually changes. Versus the “high urgency” environment, now there is no visceral utility if we take less than the scope. The scope is the goal, and ostensibly we've planned-in that much time.

There is little utility to completing it far before the scope, but there is still disutility to completing it after the scope (we don't want to seem like bad planners!), so we warp the distribution to “play limbo” with the scope.

You already see the problem. While the median in Fig 2 is probably slightly lower than the median in Fig 1, the mean is a lot higher in Fig 2. At a company, we mostly care about the mean since we're constantly pushing new things out. So simply introducing the scope has made us move slower.

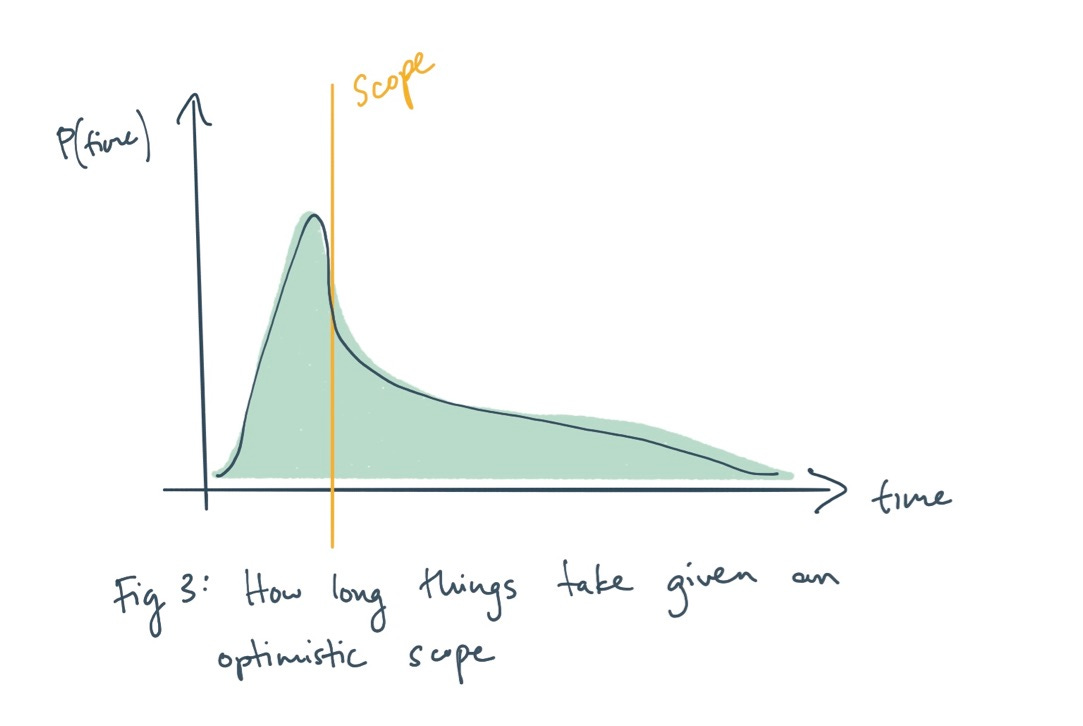

Now, what happens when we introduce an optimistic scope? Let's say we set a scope that we think corresponds to the 10th percentile of outcomes:

The mean to this distribution is still probably higher than Figure 1 (the “high urgency” environment), but not by too much more. In 10% of outcomes, we might go a bit slowly, but after that we still are “under the gun” and try to get it done. So, now with an optimistic scope, we're actually moving quite a bit faster. Put another way, optimism shapes reality.

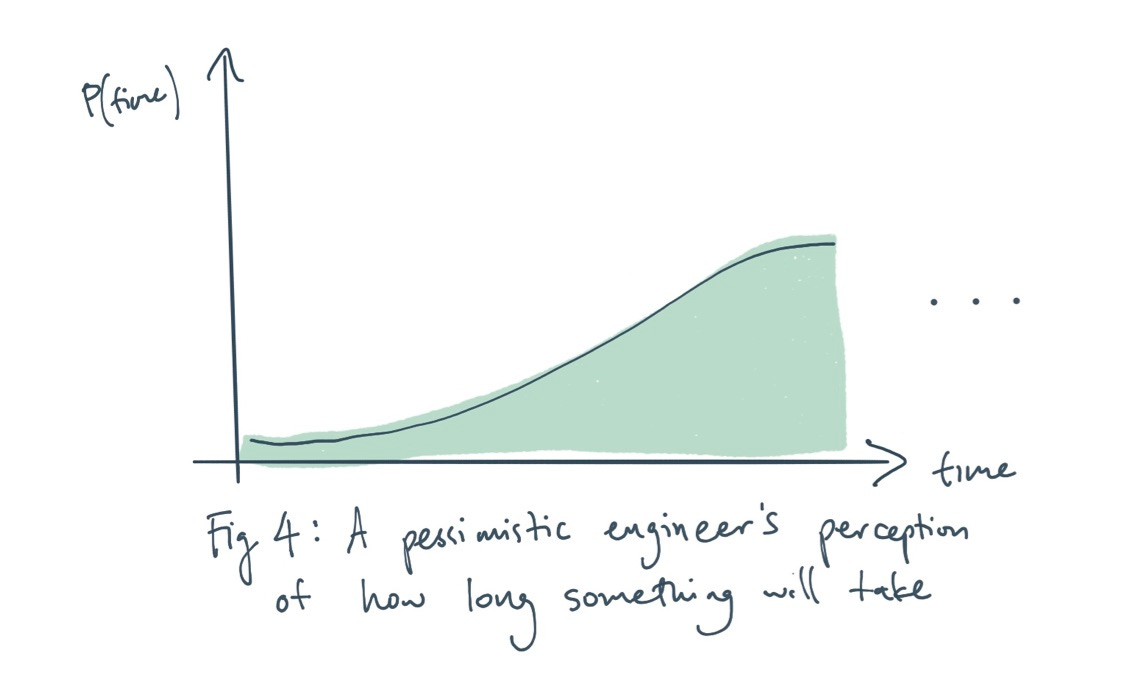

One assumption here was also that engineers are good at estimating the distribution of how long something will take. Unfortunately, that's actually pretty hard, and due to the incentive structure (it's far worse to under-scope than over-scope in most product teams), most engineers end up being pretty pessimistic in their scopes. And, with a pessimistic distribution over outcomes, stuff only looks worse.

To end, this directly ties into two of our credos at Scale AI: “Up the tempo” and “Ambition shapes reality”. Doing things as fast as possible, without regard for the scope, is the only antidote against the Limbo Effect. Optimism is another less good antidote, and if you are deeply optimistic, you can use it to consistently limbo under your goals, and over time, warp reality.

This effect might seem small in isolation, but it’s death by 1000 papercuts. A dearth of optimism will slowly kill any product, team, or mission. Execution will slow to a halt, and even the most minor tasks takes weeks to do. Our optimism and resolve have immense influence in what we accomplish, both at a micro task-by-task level, and when summed up, what we can do over a lifetime.

This is something that many others have understood well, and that has led them to achieve the outer reaches of reality. A quote from Steve Jobs:

I've learned over the years that when you have really good people you don't have to baby them. By expecting them to do great things, you can get them to do great things.

My greatest wish for all the doers and makers in the world is the allow your optimism shape your reality—it will serve you well.